Verification Is Not Validation: Drawing the Line Clearly

In regulated software development, there's a dangerous temptation: building tools that do everything. Tools that verify data integrity, interpret results, suggest corrections, and verify outcomes—all in one convenient package.

This sounds efficient. It's actually unsafe in regulated contexts.

The Olexian Evidence Platform (OEP) takes a different approach: strict scope limitation. OEP verifies evidence bundles. It does not validate scientific correctness. It does not interpret results. It does not certify safety. And this refusal to do more is precisely what makes it trustworthy.

Let's explore why narrow scope isn't a limitation—it's a safety feature.

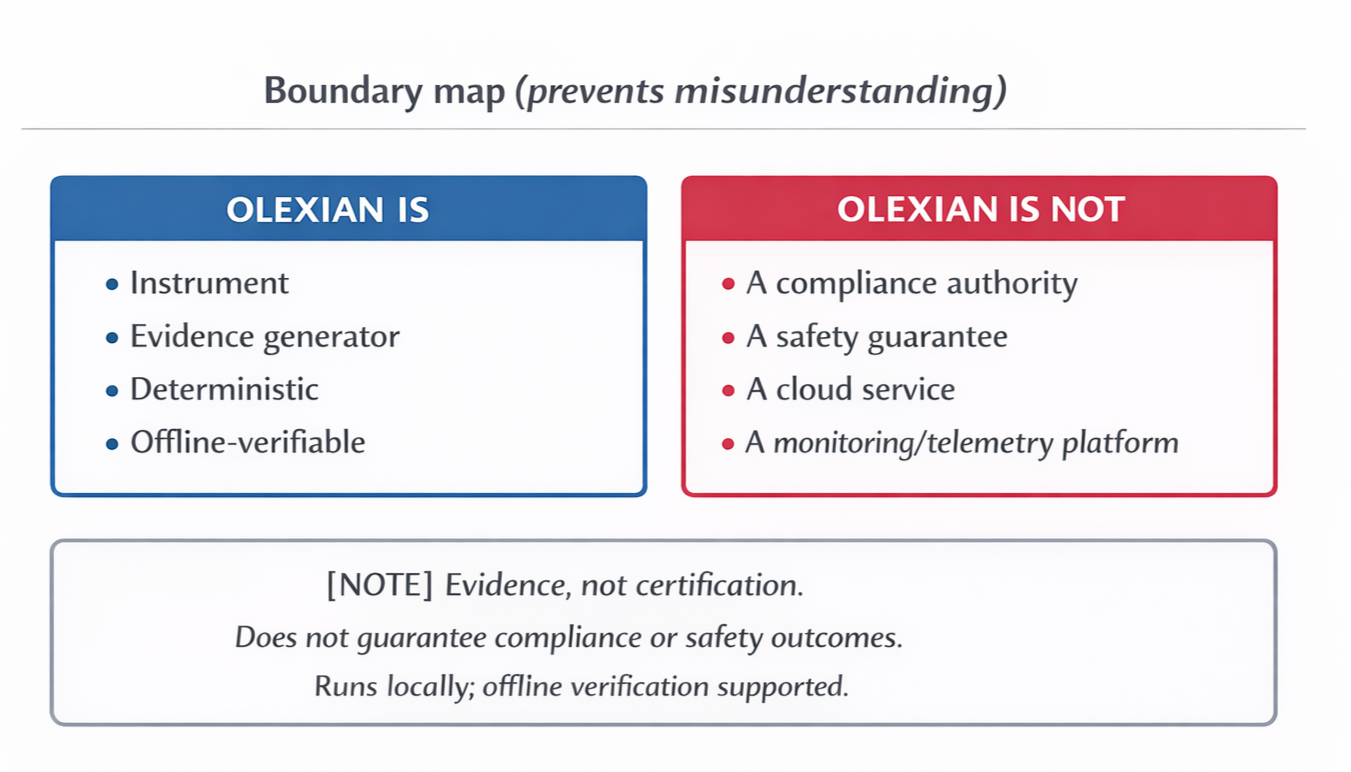

Boundary Map:

Left is a clear boundary diagram showing what Olexian Instrumentation is and is not, clearly separating evidence-producing capabilities from compliance, safety, cloud, and monitoring claims.

The Verification-Validation Boundary

In systems engineering, verification and validation are distinct concepts:

Verification asks: "Did we build the thing right?" (structural integrity, contract conformance, reproducibility)

Validation asks: "Did we build the right thing?" (correctness, effectiveness, fitness for purpose)

OEP sits firmly on the verification side. It can confirm that:

Your evidence bundle is structurally intact

Declared hashes match observed content

Required artifacts are present and schema-conformant

The bundle was produced under a declared contract version

OEP cannot and will not confirm that:

Your algorithm produces scientifically valid results

Your measurements are accurate or meaningful

Your outputs are safe to use in a clinical context

Your system complies with any specific regulation

This isn't a bug. It's the design.

The Danger of Blurred Boundaries

What happens when verification tools cross into validation territory?

1. False Authority

A tool that reports "verification passed" and also interprets results creates ambiguity. Does "passed" mean the data is intact, or that the results are correct? Users conflate the two, and suddenly a structural check becomes a safety certification.

2. Scope Creep in Liability

If your verification tool makes claims about result correctness, it inherits responsibility for those claims. Now you're not just verifying structure—you're certifying scientific validity, clinical safety, or regulatory compliance. The legal and technical burden explodes.

3. Single Point of Failure

When one tool does everything, there's no independent check. A bug in the verification logic also corrupts the interpretation. Separation of concerns isn't just good software design—it's a hazard control.

4. Regulatory Classification Risk

Medical device regulation often hinges on "intended use." A tool that merely verifies data integrity may fall into a lower risk class. A tool that interprets clinical data and suggests actions? That's potentially a medical device subject to much stricter controls.

By staying in the verification lane, OEP is designed to avoid providing clinical decision support features that can increase regulatory burden. Classification depends on intended use and system context.

Why Refusal Increases Trust

Counter-intuitively, doing less can make a tool more trustworthy. Here's why:

Clear, Testable Claims

When OEP issues a verification evidence bundle, the claim is narrow and testable: "This bundle's structure conforms to the declared contract version, and these hashes match." You can independently verify that claim. You can't easily verify a claim like "this algorithm is clinically safe."

Composability

Because OEP doesn't interpret results, it can work upstream of your validation process. You verify integrity first (OEP), then validate correctness separately (domain experts, statistical analysis, clinical review). Each layer has a clear responsibility.

Auditability

During an audit, you want to show what happened, not justify why it was right. OEP provides the "what happened" artifact: provenance, custody chain, integrity proof. Your validation documentation provides the "why it was right" evidence. Keeping these separate makes audits clearer.

Fail-Safe Posture

OEP verification can fail for structural reasons (missing artifact, hash mismatch, malformed manifest) without making any statement about result quality. If verification passes, you know the bundle is intact—but you still need to validate the science separately. This prevents a false sense of security.

The Hazard Boundary in Practice

Let's make this concrete with examples:

Safe: Verification Lane

"The bundle contains 47 artifacts with matching hashes."

"The manifest declares a supported contract version."

"All required schemas are present and valid."

"Verification completed deterministically; evidence hash: [value]."

These statements are observable facts. They don't require domain expertise to evaluate, and they don't depend on clinical context.

Unsafe: Crossing into Validation

"The diagnostic accuracy is 94.2%." (Interpretation)

"This result is clinically significant." (Judgment)

"The device is safe for patient use." (Safety certification)

"This complies with FDA requirements." (Regulatory claim)

These statements require domain expertise, clinical context, and regulatory knowledge. They carry liability. A verification tool has no business making them.

Scope Limitation as Risk Control

By staying narrow, OEP achieves several risk-control objectives:

1. Reduced Attack Surface

OEP is intentionally narrow: it verifies declared artifacts against a contract, and refuses anything missing, unknown, or altered.

2. Stable Verification Logic

Clinical algorithms evolve. Regulatory standards change. Scientific understanding advances. But the rules for "is this hash correct?" don't change. By limiting scope to structural verification, OEP's core logic can remain stable across years—critical for long-term auditability.

3. Customer Flexibility

Because OEP doesn't interpret results, customers can use it across different domains: diagnostic imaging, genomic analysis, sensor calibration, environmental monitoring. The verification logic is domain-agnostic. Customers bring their own validation expertise.

4. Clear Responsibility Boundaries

When something goes wrong, scope limitation makes responsibility clear:

Verification failure (missing file, hash mismatch) → OEP detected a custody problem

Validation failure (incorrect diagnosis, poor accuracy) → Customer's algorithm or process issue

No ambiguity. No finger-pointing. Each component has a clear job.

What This Means for Integration

If you're integrating OEP into a larger system, here's the mental model:

[Data Collection]

↓

[Evidence Bundle Assembly]

↓

[OEP Verification] ← You are here (integrity check only)

↓

[Domain Validation] ← Your responsibility (correctness)

↓

[Clinical Review] ← Your responsibility (safety/effectiveness)

↓

[Regulatory Submission] ← Your responsibility (compliance)

OEP handles one step: verification. Everything else is yours. This isn't a limitation—it's a feature that lets you compose a system with clear separation of concerns.

No Clinical Decision Support Outputs

OEP's documentation explicitly states:

OEP does not generate clinical guidance, dosing, diagnoses, alarms, or treatment recommendations.

This isn't legal boilerplate. It's an engineering constraint that shapes the entire design:

No patient-specific outputs

No automated clinical actions

No interpretation of clinical significance

No claims about medical effectiveness

By staying on the verification side of the hazard boundary, OEP outputs serve as engineering evidence and audit artifacts—not clinical decision support.

This positioning matters for regulatory considerations, but the determination is always customer-specific, based on the complete system context and intended use.

OEP doesn't make classification claims. It simply provides the facts: here's what was verified, here's what was not.

When Narrow Scope Isn't Enough

Let's be clear: verification alone doesn't make a system safe or compliant. You still need:

System-level validation: Does your algorithm work correctly?

Clinical evaluation: Is it safe and effective for the intended use?

Risk management: Have you identified and controlled hazards?

Regulatory compliance: Do you meet applicable standards?

Quality management: Can you maintain this over time?

OEP supports these activities by providing deterministic, auditable verification artifacts. But it doesn't replace them.

Treat any claim that verification eliminates the need for validation or compliance work as a red flag.

Building on a Narrow Foundation

The power of scope limitation becomes apparent when you build on top of it:

Independent Review

Because OEP verification is narrow and deterministic, external auditors can re-run verification without needing domain expertise. They're checking custody and integrity, not scientific validity.

Modular Upgrades

When your clinical algorithm evolves, OEP verification logic doesn't need to change. The interface between verification and validation remains stable.

Multi-Domain Reuse

The same verification tool can support genomics, imaging, sensors, and environmental monitoring—because it doesn't interpret domain-specific content.

Defensive Depth

When verification and validation are separate, you get defense in depth. A bug in your algorithm doesn't corrupt verification. A verification failure doesn't imply your algorithm is wrong—just that something unexpected happened to the bundle.

Conclusion: The Discipline to Refuse

Building a verification tool that refuses to do more is harder than it sounds. There's constant pressure to add "just one more feature" that interprets results or certifies correctness.

Resisting that pressure requires discipline. It requires saying "no" to feature requests that blur boundaries. It requires accepting that your tool will do less than competitors who promise to solve everything.

But in regulated contexts—especially medical software where trust and auditability are paramount—narrow scope isn't a weakness. It's a strength.

OEP's core principle:

Verify structure and custody. Refuse to judge correctness. Trust emerges from clarity, not comprehensiveness.

When your evidence bundle verification tool sticks to its lane, it becomes a reliable witness in your audit trail—not another source of uncertainty.

And in a world where complex systems fail in complex ways, that reliability is precisely what you need.

For inquiries, contact the OEP team.